- The stock market parallels with the conditions of 20 years ago are hard to miss, according to top investors.

- A U.S. economy growing nicely at full employment in an unusually long expansion, the Fed is tightening methodically, big growth stocks dominate amid talk of New Era in tech as "disrupted" sectors suffer and a deal boom featuring huge media mergers is rolling.

- The rhymes between today and the late-'90s are close enough that some veteran market participants like Paul Tudor Jones are singing along.

Getty Images

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg speaks during the F8 Facebook Developers conference on May 1, 2018 in San Jose, California.

Reminders of the late-1990s are appearing all over Wall Street these days, and not just the return of high-waisted jeans and designer-logo handbags.

The economic and financial-market conditions are drawing comparisons to the later years of the '90s, when good economic times and a technology boom culminated in a powerful bull market that went to stunning extremes before collapsing in early 2000.

No two historical moments match up perfectly, of course. But an array of features of, say, the 1997-to-1999 period are observable today: An unusually long economic expansion that began with tepid growth rates and stubbornly slow employment gains finally start to hum, reaching a phase of almost-monotonous strong performance and essentially full employment. Consumer, small-business and CEO confidence readings today are near the historic highs reached in the late-'90s.

The Federal Reserve is tightening, but not at a pace that is noticeably restraining capital-markets risk-taking. The Treasury yield curve is rather flat, but long-term yields are still almost half a percentage point above the two-year. Emerging-market stock and bond markets start to wobble under the strain of Fed tightening and dollars shuttling back into the U.S., triggering some global market scares but also keeping the Fed more cautious than it might otherwise be.

A stock market dominated by Big Tech shares riding promises of a glittering digital future hovers near record levels, while a crowded purgatory of stocks of companies deemed "disrupted" struggle. A media merger frenzy gets rolling, featuring an acquisition of Time Warner as its signature bold stroke.

The rhymes between today and the late-'90s are close enough that some veteran market participants are singing along.

Seen this movie before?

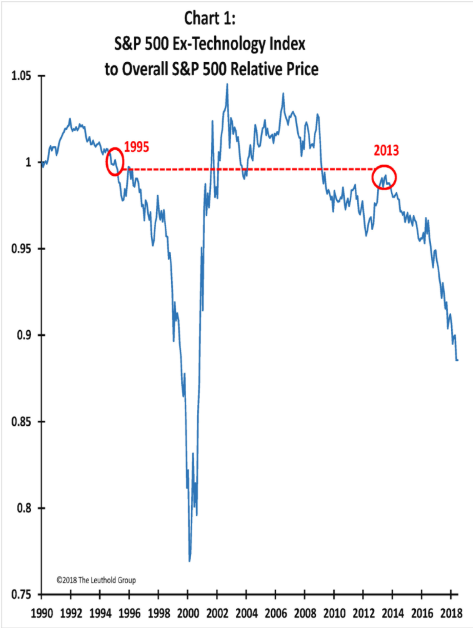

Jim Paulsen, strategist at Leuthold Group, produced this chart showing the sharp underperformance of non-tech stocks versus the tech leadership. The pattern is roughly similar though the magnitude of tech domination isn't as extreme now.

Source: Leuthold Group

"Haven't we seen this movie before?" Paulsen asks. "Technology takes over the stock market late in a recovery cycle, seemingly making the bull ageless, pushing portfolios toward a more concentrated new-era exposure, stimulating investor greed bolstered daily by watching a chosen few (FANGs) rise to new heights, and convincing many that tech is really a defensive investment against late-cycle pressures which trouble other investments."

Celebrated hedge-fund trader Paul Tudor Jones in a CNBC interview this week compared today's environment with others such as the U.S. market in 1999, when stocks kept rising even as the Fed tightened — until the Fed finally had to get aggressive and choke off the surge.

"I think the stock market also has the ability to go a lot higher at the end of the year. ... I can see things getting crazy particularly at year-end after the midterm elections ... to the upside," Jones said.

Another school of market-cycle analysis looks at the 2008-2009 financial-crisis meltdown as analogous to the 1987 stock-market crash, in terms of collective psychic damage and the effect on risk appetites — even though they differed in magnitude, duration and economic impact. It was a full decade after the '87 crash before the public truly began to embrace a fast-rising stock market, for what that's worth.

Changing the 'rules' for tech

There are perhaps some other, more subtle developments that with the benefit of hindsight reflected an overconfident Wall Street willing to change the rules of the game in the late-'90s.

After avoiding big Nasdaq stocks for years, the keepers of the Dow Jones industrial average succumbed and added Microsoft and Intel to the venerable index on October 1999 — six months before the peak. This year, S&P will reshuffle its sectors to create a new communications-services sector to capture all the Internet stocks now in telecom, consumer discretionary and tech — perhaps feeling the formal tech sector is getting too unwieldy.

And some look back at the passage of Regulation Fair Disclosure in the year 2000, requiring companies to release all material information publicly, and believe the end of quiet massaging of investor expectations caused a jarring uptick in volatility just as a bear market was taking hold. Now we have a budding effort by Warren Buffett and Jamie Dimon to end quarterly public earnings guidance.

With all those parallels to the late-'90s traced out, it's important to point out several crucial differences, which together make the current market seem less overheated and hazardous than, say, 1999.

For one, stocks just aren't up as much and investors' speculative energy is not as wild today. The annualized total return for the S&P 500 over the past five years is 14 percent, and the annual return for the past ten years 10.5 percent. From 1997 to 1999, the trailing 5- and ten-year returns were twice as high.

Speculation? In 1999, there were more than 500 IPOs and their average first-day share-price gain was almost 70 percent. We have nothing like that today.

Valuations today are high, but not as high as back then. The dominance of tech stocks today arguably better reflects the pervasive role of the most powerful tech platforms in the economy and daily life. Back then, most companies were flimsier operations with unproven business models.

As an example, when AOL reached a $200 billion valuation in early 2000 as it agreed to merge with Time Warner, it had a mere 20 million subscribers and no real earnings. Facebook, at a $550 billion market value, has 2 billion users and last year earned $16 billion on $40 billion in revenue.

Even the way the stock market backed off early this year after a relatively brief phase of exuberant upside shows this to be a more orderly, less heedless market than the very end of the '90s.

All of which is to say, if this market cycle is eventually going to become a true rerun of the late-'90s — and there's a good chance it never quite will, in many respects — there is still a good way to go before it gets there.